Undrea “Gem” Jones was released from prison after 21 and a half years on Feb. 26, 2019. She always knew she would go back in — but as a volunteer for the Storybook Project of Arkansas. She wants to be a part of helping parents and grandparents form and foster bonds with the children in their lives the way volunteers helped her.

“It was a momentous event for me because it was coming full circle,” she said. “That was a whole experience that I had been waiting to have for a very long time.”

Jones was sent to prison for a crime she committed at the age of 16. Her son was 2 years old. The Storybook Project of Arkansas, a nonprofit prison outreach that allows volunteers to record inmates reading to their children, was already underway at the Arkansas Department of Corrections-McPherson Unit when she arrived.

Experts, like those from the American Academy of Pediatrics, point out that reading to children not only boosts their language skills, it also strengthens their relationships with their parents.

Books have seen Jones through some of the hardest times in her life, including her own childhood.

“I love books. I excelled in academia,” she said. “There was a lot of trauma that I was dealing with at that time, and books were a safe-haven for me. I read anything that transported me from my present circumstances.”

She couldn’t physically pull her son onto her lap and snuggle him for reading time while she was in prison, but the Storybook Project of Arkansas allowed her to give him the gift of her voice.

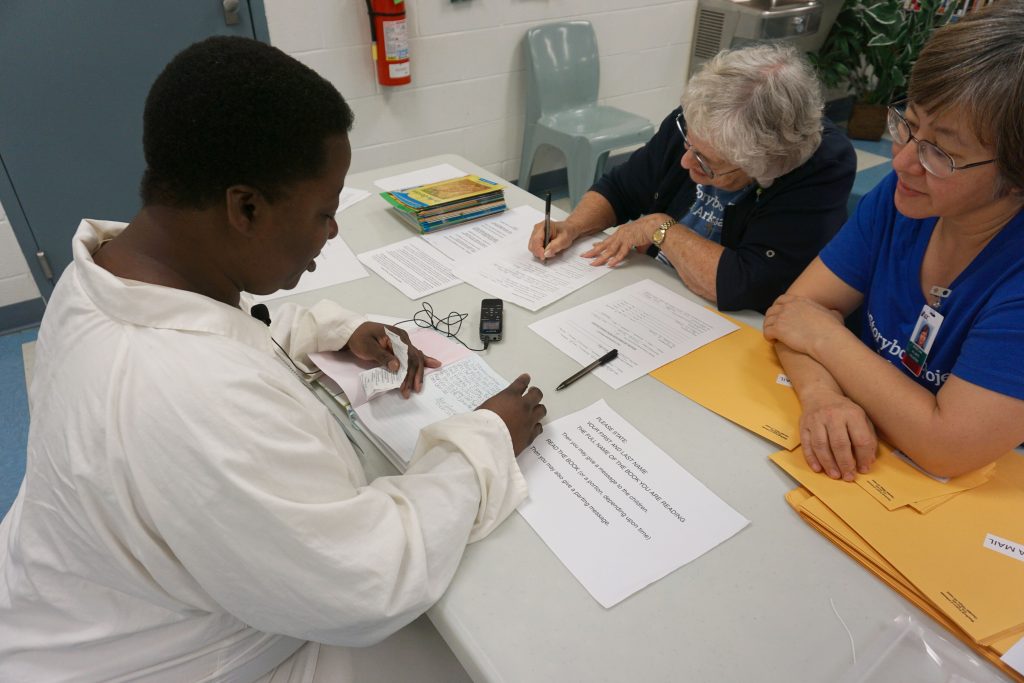

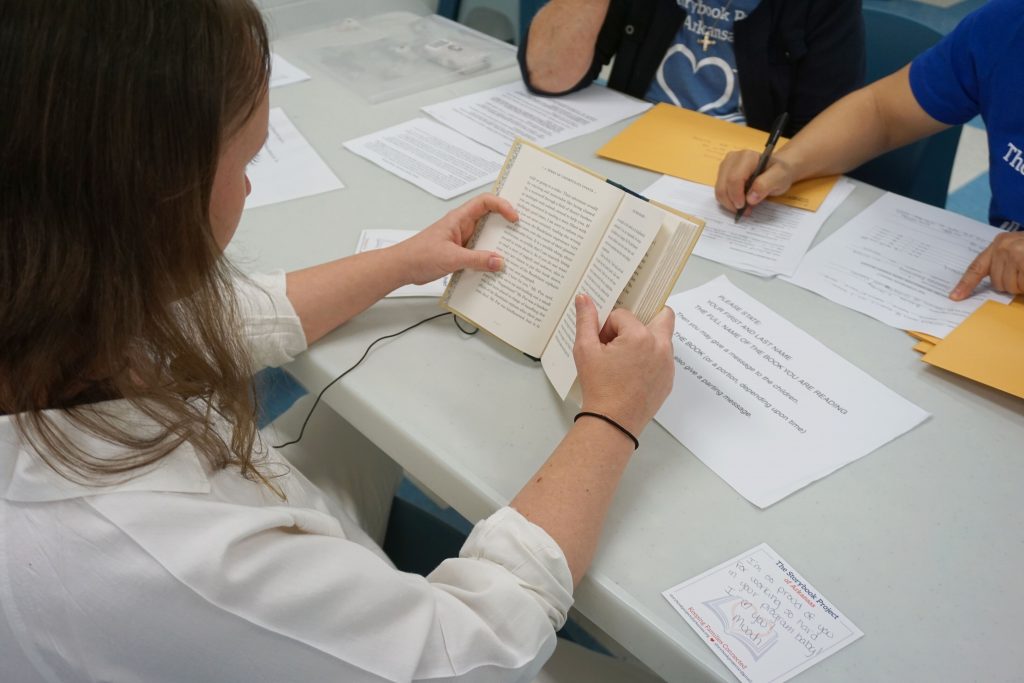

Jones and other volunteers from the outreach visit prisons four times a year, said Denise Chai, who leads the Arkansas program.

“We bring in a whole bunch of books, and they choose one,” said Chai. “They will write a message in the book, and then they go and sit down with a volunteer and they’re recorded, giving a message Then they read the book and give another message at the beginning. After we leave the prison, we burn that to a CD, because we’re not quite digital, and we mail the book and the CD to the child.”

Jones doesn’t remember any of the books she chose to read to her son.

“I don’t remember the books because you’re going through so much in the process at that moment,” she said. “It’s amazing, but it’s also really difficult because you want to say so much to your child, but at the same time you want to hold it together and send love and encouragement, and you’re holding a broken heart because you can’t be there. You would have to prepare yourself so you would not be overcome with just the gratitude and appreciation and broken-heartedness — and get through it.”

Choosing books to share with him, however, was simple. “I heard another volunteer say we had so many different, beautiful books, and she said, ‘How do they choose which book they want to read?’” said Jones. “I said, ‘The book chooses us.’ During the whole process as my child grew older, I found a book always picked me for what I was going to read to him.”

She remembers asking him to read a book about Puerto Rican evangelist Nicky Cruz when he was old enough, and to let her know what he thought of it. She didn’t read the book to him, but he did write a report to share his thoughts when he finished on his own.

“He had the foundation of reading from the storybooks that I sent him,” she said.

That book, like others they shared during her sentence, created common ground for them, helping foster a bond that can be lost when parents and children are separated for long periods.

Jones considers herself lucky because some of the people she met in prison didn’t have custody of or contact with their children; her son was in the care of family, and they made sure he heard about her and that she saw him when possible. The recordings he received of her reading to him linked them while they were apart, sometimes serving as conversation starters when they could be together.

She hasn’t discussed the Storybook Project with her son and won’t hazard a guess about what it might have meant to him. She is a proud mom, though.

“My son has a love of academia, and he went to college on an academic scholarship. He loves knowledge,” she said. “He is career-focused, and he’s in a committed relationship. He has never been touched by the criminal justice system. He is an awesome man.”

The Storybook Project, she said, helped her be a better mother.

“It wasn’t just about reading a book or sending a book or recording to our child,” she said. “To us, it’s everything. We get to send a piece of ourselves to our children, some of them we haven’t ever seen, some of them we haven’t seen in years or months,” she said. “That one moment that we got the opportunity to be a normal parent was —– is — just something that is priceless.”